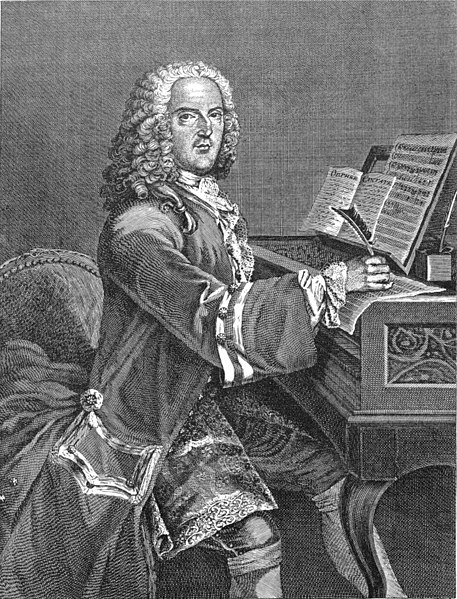

In 1710 Louis-Nicolas Clérambault published a Livre d’orgue containing two suites (Suite du premier ton et Suite du deuxième ton) in the style of the french organ school. I’m working on a couple of pieces of the latter one. The first piece is a Plein Jeu which I’m playing for almost two years now, and I’m still not content with the outcome. This posting tells why.

At first sight, the piece is not that difficult to play. Just two pages of sheet music, partly even without pedaling, and only a couple of sixteenth notes. Actually I did not notice any issues until I mastered playing the piece mechanically and started interpreting it. What I was playing at that time just was sounding dull. It was obvious that the composer had things in mind I didn’t understand yet.

Speed

The piece is structured in four parts. It starts with the «Petit plein jeu au positif» (without pedaling), in bar ten it swaps to the «Grand plein jeu» (with the pedalboard joining in bar 13), back to positif in bar 22 and back in bar 32. A couple of things happen at the interfaces:

- The keybed changes.

- The time signature changes between “2” and the infamous alla breve.

- The parts on the Positif are marked as «Gay»ment, the parts of the great as «Lentement» (or even «fort lentement» for the last couple of bars).

I was confused by the latter two points. Fortunately I found some additional information concerning french Plein Jeux in the book »Zur Interpretation der französischen Orgelmusik«. Beginning with page 14, Hans Musch cites several contemporary composers:

- Nicolas Lebègue: «Le Prélude et Plein Jeu so doit toucher gravement, et le Plein Jeu du Positif légerement.»

- André Raison: «Le grand plein jeu so touche fort lentement. […] Le petit plein jeu je se touche légèrement et le bien couleur.»

- Jacques Boyvin and Gaspard Corrette both state the agility applied to the positif, e.g. by using trills.

After a lot of experimenting I’m currently using the following approach. I interpret the «2» of the positif as a time signature of 2/2. I use a speed of 56 beats per minute, which is equivalent to a speed of about 112 bpm in case the time signature was 4/4. And I interpret the alla breve of the grand plein jeu as a 4/4 using the very same pulse of 56 bpm. This actually means a bar of the grand plein jeu has twice the duration of a bar on the positif. This allows me to keep a steady pulse throughout the complete pièce while still playing the positif twice as fast as the grand plein jeu. This is exactly the opposite of what an organ player might do when only reading the sheet music.

Steady Pulse

A steady pulse, which guides the listener through a piece, is a very important aspect of a good interpretation. I try to keep the aforementioned tempo of 56 bpm throughout the piece, except for the last couple of bars. This is hindered by a couple of issues. One of the impediments are the trills (e.g. bars 1,2, and 22 ), another the rests before the sixteenths (e.g. bars 1, 2, 10, 16, 17, 18, 19). A further issue is the relative length of the sixteenth notes. Especially on the grand plein jeu, I tend to play the sixteenths way too fast. But the very same is valid for the quarter notes. Frankly, it actually is difficult to play the quarter notes as slow as necessary. I always feel like «Those can’t be that long».

I’m currently experimenting with a metronome to educate myself. Interestingly, I’m now playing the second petit plein jeux part (bar 22) much slower than before. And it is difficult. I do not intend to play the piece exacly like this, since Agogic is an important part of an interpretation. But for the moment it helps me to figure out a correct straightforward approach. It’s just the baseline before applying some deviations.

Notes inégales

In short, the piece sounds boring without them. Since the meter is even, notes inégales can be applied to the notes of one quater of the “denominator”. On the petit plein jeux, those are the eighth notes. But what about the grand plein jeu in alla breve?!? I only see one solution, which is applying notes inégales to the eigth notes on the main as well (e.g. bars 14 and 15).

The infamous last line

I had difficulties to bring the last line to life. Until I started to apply notes inégales to it as well, though the typical rules of notes inégales are not obviously visible. But they helped a lot. Beginning from the 2nd half of bar 42 until the end of the pièce, I have to count the triplets loudly to cope with this issue. But it’s well worth the effort. Since I treat the eigths notes as the thirds of a triplet, I get much better results. I keep it this way even during the ritardando of the last three bars. And I still apply them to the trill on the very last half note.

Plein Jeu, Grand Jeu – Grand Plein Jeu!

The french organ school of that time knows the Plein Jeu as the choir of principals (including mixtures), and the Grand Jeu as a combination of labial and lingual stops. As far as I know at the moment, they neither didn’t know of a Tutti nor a combination of the Plein Jeu with the Grand Jeu. The only exception I know of is the Plein Chant, a Plein Jeu with a 8′ Trompette added to the pedal.

The mistake I made was to interpret the term “Grand Plein Jeu” as the combination of a Plein and a Grand Jeu. Meanwhile I dismissed this practice. It just means the Plein Jeu of the great organ in contrast to the Plein Jeu of the positif. Note that a Plein Jeu also requires the positif to be coupled to the great organ.

Verdict

A lot of difficulties, well worth the effort. French organ masses consist of relatively short pièces. And every pièce is different of all others. Yes, it’s a lot of work to fiddle with the characteristics of all those short piéces. And this is what makes baroque french organ music different. There’s a lot of stuff densely packed into relatively short pièces. I’m deeply impressed what the musicians of that period have to offer. The longer I spend time coping with their music, the more I believe they anticipated jazz music – centuries before it was invented.