Since last year I learned new techniques to master the music I play. I first applied them to some pieces I was already playing, so that this year’s performance went quite well. After almost one year I thought it was time to apply them to learning a new piece.

As Jon Laukvik writes in his book:

Der Übeprozeß führt, spieltechnisch gesehen, vom bewußten Tun zum unbewussten Geschehenlassen.

Freely translated:

From a playing perspective, practising leads from conscious doing to let it happen unconsciously.

The key to it is muscle memory (»Prozedurales Gedächtnis« in german). To train it, I do repetition a lot. To gain the required motivation to do so, I had to learn that playing a piece of music is a totally different thing than practising it. Besides many other sources I used, I can recommend the TEDx talks of Jocelyn Swigger and Claire Tueller.

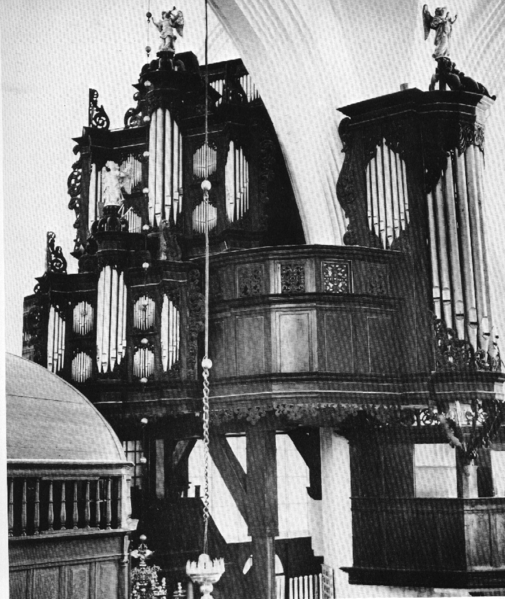

The new piece I’m currently applying it to is a Fantasia (e minor) of Abraham van den Kerckhoven. Here’s the approach I’ve chosen.

Prepare interpretation

The interpretation I intend has some impact on the fingering. E.g. if I want to play a couple of notes in legato style, I may use another fingering as if I want to play staccato. The difficulty is that I do not yet have a clear picture concerning the interpretation, since this will develop as I learn the piece. But anyway, sometimes I already have some ideas how to interpret some bars, and most often I already have an idea how not to interpret some bars. I do this by learning more about the context in which the piece was written (composer, time, location) and by listening to interpretations of other musicians.

Develop fingering

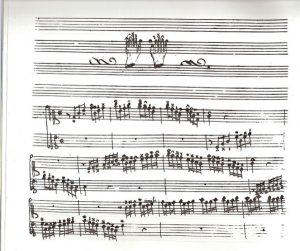

Muscle memory is trained by repeatedly doing the same motions. This requires to play each individual note of the piece with the very same finger each time. I do not write down the number of the finger for each individual note. But I apply enough numbers so that the fingering is absolutely non-ambiguous.

This can become a very frustrating process. I have to “somehow” play the piece while considering how I could do the fingering and writing it to the sheet music. Often there are passages where I have no clue yet how the fingering should look like, but I must decide for one before I can practise it. Some things I do:

- When I found some fingering but dislike it, I start practising whith it anyway. It may well happen that I change it at some later time, when I learned more how I want to interpret the piece. This means that I will need to re-learn the new fingering. But if I have no better clue right now, I accept this possibly additional work.

- I try to avoid fingerings where I have to jump with the very same finger from note to note. But sometimes it turns out later on that there either is no better solution, or that the jumping fits the interpretation rather well.

- Sometimes it is difficult to find a good fingering playing the notes forward, e.g. because I want to reach a later note with a certain finger. In such cases, I develop the fingering backwards, playing from right to left.

At the end of the process, the sheet music is quite populated by a lot of magic digits, which is the base for training the muscle memory.

Define fragments

The next step is to divide the piece in relatively short fragments which I can practise independently. I apply numbered markers to the sheet music. The length of the fragments depends on a couple of parameters, e.g. the structure and difficulty of the piece. Sometimes a fragment is just one or two bars, sometimes approximately one line. Sometimes I start with short fragments and I make them longer at a later point in time – or the other way around in case it turns out a passage is more difficult to learn as expected.

Practise fragments

Practising is the process which absolutely consumes the most time while learning a piece. As a consequence, I apply several techniques to succeed.

- Remove any distraction. I never sit down to the instrument as long as any other stuff occupies my mind. I write down any other ToDos so as to avoid that they pop up during practising. I ensure noone else is listening, e.g. by using an electronic instrument and headphones, since otherwise I am not really free in focussing on the music.

- Limit session time. Some people use a timer to limit the sessions. I do not. Instead, I define the scope, e.g. the amount of fragments I want to practise. For shorter pieces, this may well read as ”Practise each fragment at least twice”.

- Prefer multiple shorter sessions over one long. It is being said the brain learns in the time between the sessions. Thus I practise for about 20 minutes up to an hour, then I do anything different, and return to the instrument after an hour or so.

- Practise in slow motion. To train muscle memory, I play the fragments in ultra slow motion. This may be half of the target speed. For me it is difficult to resist the temptation to speed up. But I know doing so is counter-productive. I keep the speed constant at least during one session.

- Use a metronome. I often listen to organ music which is played with little rhythmical structure respectively missing pulse. For me it is absolutely key to exactly know the rhythm of each individual fragment. The metronome has a further side effect – it prevents me from raising the speed during the session. As we are at it – I found that many many metronome apps for Android are not running precisely. Use one with proper timing. I built a spike for my own which I’m constantly using, but it’s only available as source code, not via the play store.

- Limit repetitions. As a rule of thumb, I notice my concentration for each fragment already decreases after a couple of repetitions, e.g. three to four. As a consequence, I usually do not repeat a fragment more often. However, I sometimes break this rule, especially with new fragments my fingers aren’t used to yet at all. It may well happen I then repeat them up to ten times.

- Focus on playing it right. Training the muscle memory best works in case the motion absolutely is identical each time. In case I notice my fingers prefer another motion over the fingering I developed, I sometimes change the fingering to reflect that.

- Practise fragments in random order. The goal is to avoid that the brain learns it can rely on the sheet music. I thus practise them in random order.

- Practise fragments at the end of the piece first. Pieces sometimes become more complicated to play towards the end, and even if not, chances are given I did practise the fragments at the beginning of a piece more often than the later ones, resulting in the fact that I can play the beginning of the piece better than the end.

- Practise fragments difficult to play the most. In case I won’t master those, any other effort to learn the piece is useless.

- Practise on different instruments. Different instruments provide different key sizes, key action, key weight and so on. I use this technique to gain reliability. Fortunately the Kerckhoven piece lacks a pedal voice, so I can just practise it on a piano.

- Practise with dynamic sounds. I’ve chosen a synthesizer sound on my digital piano which provides lots of dynamics. This way I can easily detect notes I depress with less precision than others. Those notes require additional attention, since they indicate weak fingering.

- Do not play the complete piece too early. This is an temptation I do not resist very well, since it helps to develop my interpretation, which in turn can lead to changed fingering. So I do play the piece every now and then. But at least I try to pay attention to the next point.

- Clearly separate playing from practising. Since the brain learns during the rests, I never play the piece the day I practised. If I want to play and practise the very same day, I always do the playing first.

Conclusion

I know about a couple of further, more advanced techniques, which I apply every now and then. But the abovementioned points meanwhile became essential to me and allowed me to make significant progress within a couple of weeks while learning Kerckhoven’s piece.

I wrote this posting due to the fact that I found rather little information concerning this topic, though it is important to so many people who play instruments either professionally or as an amateur. If you know about similar documents, please let me know.